Lean executive coaching

I often get asked “how do you move from gemba coaching to executive coaching?” which I find kind of surprising because the whole point of executive coaching is to get execs to the gemba, looking into the details, discussing with people and trying to understand how frontline teams interpret the executive strategy.

Lean aside, how does one coach an executive, period. I mean: if someone else knows how to do the job better, why don’t they do it? On the other hand, we have all benefited from a second pair of eyes and an outside perspective, so why not executives as well?

Personally, the breakthrough step was to learn to formulate hypotheses rather than have opinions. You can’t nothave opinions. They pop up in our minds fully formed and they feel real as real – this is how minds are made.

But the human mind also has this amazing ability to construe some form of “objective” perspective. Children recognize false beliefs very early one, in others but in themselves as well. It takes some mental effort, but we all have the capability to add “I could be wrong” at the end of any statement.

The trick is to make it a method. Once you’ve acknowledged your intuitive opinion, you can think past it and ask yourself: what are the most reasonable hypotheses we can make in this situation? What are the strongest assumptions they’re making that really need testing.

Lean thinking can really help. To formulate basic hypotheses at the workplace, I ask myself:

- Why hasn’t this job not moved to the next step? If it’s in the store, why isn’t a customer buying it? If it’s in the truck why isn’t it already on the shelves? If it’s in the warehouse, why isn’t it in the truck? If it’s in production why isn’t it in logistics? And so on

- Why hasn’t this person moved on to her next step? The same question applies to people: what would they want to do next and why aren’t they doing it right now?

Then I try to answer these questions by listing the known “original sins” of the company – the historical mistakes that keep repeating themselves because they are in the DNA of the company. Coming from the outside, these aren’t that hard to spot – everyone knows them, but from the inside, these topics are taboo because the people that have taken these decisions, or whose personal attitudes are replicated in the behavior, are still around. Typical examples would be:

- Talking to customers about zero-interest features they couldn’t care less the company is keen on selling

- Promoting toxic managers everyone knows about because they do something useful for the boss

- Setting up employees to fail by micromanaging them in the guise of coaching them

- Pushing no-win deals on partners because, well, simply because we can.

These are generic illustrations, but usually the development of a company is the result of the sequence of its chief execs, the bees in their bonnet and attitudes, and whom they’ve chosen to surround themselves with, then how they react to outside events. The company’s syndromes (what the company considers natural, fair and good which in fact is counter-productive) are usually well known even if difficult to address. It’s funny how people will joke about these, or gossip, but never actually address them head-on (and punish whistleblowers).

Once you cross the “why isn’t this at the next step?” question with one of the obvious syndromes, you usually get a pretty good working hypothesis of something that could be changed without much risk.

Hypothesis in mind, you test it – means saying it out loud to someone. Feedback will be pretty quick (although not necessarily pleasant). Then you ask: what’s the one thing you can change right now? Yes, making this right is impossible now, but we can move closer to one day correcting it by changing just one thing – what would that be?

And then you can kick off the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. One change at a time, executives will learn to refine their understanding, discard their misconceptions and make it easier for everyone else just to do their job. Astonishingly, they usually also pivot in the process to adapt their strategy to market conditions – which is where real results come from.

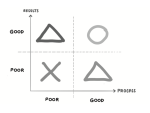

The aim of PDCA is to, first, side-step temptation of over-the-top hyper-solutions which feel good but we know won’t work, and second, look at the team first: who will have to make it work and so needs to be convinced.

The third trick to coaching, after formulating hypotheses (not opinions), testing one change at a time (to better understand the situation and the team, not to fix everything), the third trick is to start paying attention to details. Details both reveal the thinking, the commitment to quality and are the key to delivering better results. You don’t need to micro-manage people, but you do need to figure out which details need micro-managing.

It doesn’t work every time. Some executives have no intention to help the company succeed and are quite happy playing their own game. Others are simply not coachable – they will not hear something they disagree with or are incapable of changing established habits.

But for the most part, although each hypothesis is clearly wrong to start with (how can they not be), with a little luck they’re still not that far from the truth, and these discussions give the executive something to work with.

Coaching is about supporting someone to achieve goals through training and guidance. Traditionally, it’s done with “don’t do that, do this instead,” or “don’t feel that, feel this instead,” and so on. Lean coaching is unique in that it looks at orientation, not action or behavior: “look over there instead.” By revealing hidden assumptions and shoddy logic, a lean coach can help strengthen mental models by linking results to the logic driving them. When people better understand what is going on and where they fit in it, they act accordingly, by themselves.

To explore further hypothesis testing, check out The Lean Sensei.